Healthcare systems around the world are endeavoring to offer better care by reducing medical errors, through better medication management, rapid access to vital and accurate information, reduced duplication of services, access to a more comprehensive picture of health to promote advances in the diagnosis and treatment of illnesses, improved and informed decision making, and by providing continuity of care to patients. At the same time, they want to bring healthcare costs down to improve their financial futures. How is this possible?

The primary way to bridge the gaps is by using a combination of information communications technology and knowledge management to capture, code, and disseminate health information in the form of electronic health record systems that enhance care, not simply replace paper. Electronic health records have enormous potential to improve the flow of information across healthcare systems, and information is critical in the effective management of patient care. In many cases, physicians are treating patients without any background information; are unaware of previously identified conditions, including allergic reactions to drugs; and are repeating tests and duplicating the efforts of other healthcare professionals.

Electronic health records are crucial considering the frequency with which people move for economic reasons and change physicians, and also important when healthcare problems arise during business trips and vacations. EHRs will also reduce the problems associated with illegible physician notes and prescriptions, and when coupled with other alert tools, can provide the means to warn practitioners of inappropriate treatments and medication mix-ups. For example, the Canadian Institute for Health Information's annual report notes that drug errors cause approximately 700 deaths in Canada each year, deaths that were preventable simply by the implementation of an electronic drug prescription system.(1) The system removes many errors originating from poor handwritten prescriptions by providing an electronic pad for physicians to write on, which is then sent electronically to a pharmacy.(2)

In the long run, efficient use of information will reduce the cost of delivering healthcare, making it possible to offer more services and better care. The percentage of Gross Domestic Product spent on healthcare by twenty-nine members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) nearly doubled from 3.9% to 7.6% between 1960 and 1997,(3) with Canada spending 9.3% GDP in 2000 and the U.S. 13.6%.(4) In a report by Deloitte and Touche for the European Commission-Directorate General Information Society (2000), similar numbers are forecasted for Europe, with the 700+ billion euros spent in 1999 expected to double in the next five years.(5)

Patient care and expectations are also changing. Health care is becoming more complex, and more physicians are involved in the care of the same patient. The ability to share patient data through the linkage of electronic health records among different sites within the same health care system is crucial. Dr. Peter Branger of Erasmus University Hospital in Rotterdam, stressed the importance of information management and communication when he stated: "The quality of communication between healthcare professionals greatly influences the quality of patient care."(6) In The SI Challenge in Health Care, Grimson et al. write:

In addition, the single doctor-patient relationship is being replaced by one in which the patient is managed by a team of health care professionals, each specializing in an aspect of care. Such seamless or shared care depends critically on the ability to share information easily between care providers. Indeed it is the present inability to share information across systems and between care organizations automatically, that represents one of the major impediments to progress toward shared care and cost containment.(7)

In Status Report 2002: Electronic Health Records, Waegemann provides data from the Medical Records Institute's Fourth Annual Survey of EHR Trends and Usage, 2002, an international survey with respondents from United States (84%), Canada (5%), Great Britain (1%), Australia (1%), and Others (9%):(8)

When asked to identify the major clinical factors driving the need for EHR systems, physicians gave the following as the top five: improve the ability to share patient record information among healthcare practitioners and professionals within a multi-entity healthcare delivery system (90.0%); improve quality of care (85.3%); improve clinical processes or workflow efficiency (83.6%); improve clinical data capture (82.4%); and reduce medical errors (improve patient safety) (81.7%).

The AAMC Better Health 2010 Advisory Board emphasizes in its Better Health 2010 handbook that a robust information environment aids healthcare, while promoting learning and advancing science. The application of information management best practices throughout the organization, including the adoption of network-based applications that apply national standards for data definition, management and exchange; nurture an innovation culture; and involve all stakeholders in the creation and management of the organization's information environment, are all very important(9). Very important. In Enhancing Privacy and Confidentiality in the World of E-Health, a paper given at the Health On-Line Summit, in 2000, Dr. Kerryn Phelps asserts the following:

Health is not an area where advances in technology can be simply superimposed. The real limitations of e-health relate to the non technical elements: the underlying philosophy and ethics of the health profession and the complexities of the human relationships that make it work.(10)

And with more access to information via the Internet and more of their own money to spend on healthcare, many people want more say about the care they receive and have the opportunity to explore a wider range of treatment possibilities, including alternative ones. Electronic health records allow greater patient involvement in their own care, and facilitate the utilization of new tools, such as the Internet, to help people become healthier. The Internet could make healthcare treatment less dependent on place, and give it more of a 'just-in-time' flavour.

A Harris Interactive survey found that approximately 70% of consumers expressed interest in using the Internet to communicate with physicians, schedule appointments, get test results, and request drug refills.(11) The same survey found that older people were just as and even more interested than younger ones in using the Internet for health-related concerns.(12) People surfing the Internet for health information "form the largest single identifiable group of Internet users,"(13) researching, buying prescription drugs, compiling personal medical records that they own and control, and communicating with healthcare professionals.(14)

In Health Care in Canada, it is noted that in 2000, Canadians using the Internet to obtain health information more than doubled from 10% to 23%, and that 57% of households using the Internet on a regular basis, reported researching health information.(15) At a Grantmakers in Health Roundtable Meeting, held April 28, 2002 in Chicago, David Brailer of CareScience, Inc. discussed the Cleveland Clinic, which charges $800 for online healthcare second opinions. The organization earned $10 million in revenues in 2001, highlighting the willingness for some to use the Internet for healthcare applications. Again, access to personal healthcare records in electronic form is critical.(16) EHRs can empower the patient by including them in the decision-making process concerning their healthcare.(17) Healthcare will need to be patient-centered, making electronic health records the best vehicle for this paradigm shift.

In reality, very few EHR systems are installed and functioning around the world, if we exclude those used primarily for billing and ordering prescriptions. After forty years of researching and trying to develop EHR systems, why aren't they in full use?

In part, the problem originates from the very structure of medical records: they contain a variety of information types (i.e. images, unstructured text, numeric data) that are structured in a combination of time-oriented, source-oriented and problem- oriented ways, and that is very difficult to duplicate with computers.(18) Paper does allow for flexible use and is adaptable, supporting local practice and individual preferences, which is important for busy healthcare professionals. ICT-under investment is certainly a factor, considering the difficulties involved in the generation of capital needed for IT investment, since IT is regarded as an add-on cost, not an investment for competitive advantage. Skepticism among senior executives regarding benefits vs. return on investment is also prevalent.

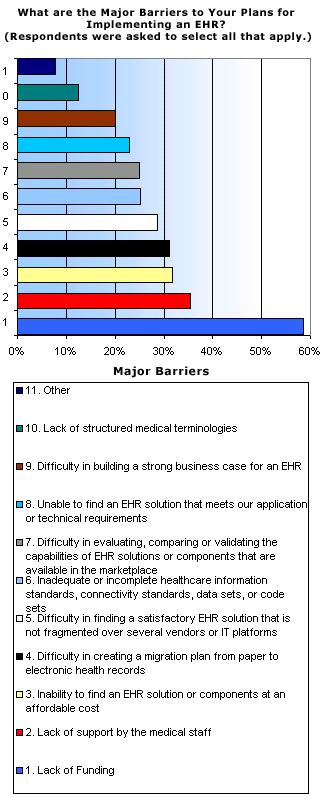

Certainly, lack of resources is a huge barrier. The Fourth Annual Survey of Electronic Health Records (EHRs) Trends and Usage study reported that 58% of the respondents cited the largest barrier to implementing an EHR was lack of adequate funding or resources.(19) A full electronic health record system, including a picture archiving and communication system (PACS) can cost tens of millions. Hardware and software is very expensive, especially if you factor in the costs of future upgrades. Other technology problems include: the lack of broadband communication networks, lack of a standard code of generally accepted practices and protocols, poor user interface design, lack of appropriate vocabulary and data transmission standards, the challenges surrounding entering data, concerns about data privacy, confidentiality, and security of health information, and ensuring access only to authorized users.

We also must recognize that implementation of an EHR means great change for those working in the healthcare sector. Organizational and change management issues relating to the introduction of IT systems are difficult to manage in a clinical environment. Cultural issues and resistance to change, perhaps most importantly, resistance from physicians, many of whom are independent contractors, is something to factor into electronic health record initiatives.

The Fourth Annual Survey of Electronic Health Record (EHR) Trends and Usage, sponsored by the Medical Records Institute (MRI) and SNOMED« International, surveyed respondents between April 15, 2002 and May 16, 2002. Lack of adequate funding or resources; lack of support by the medical staff; inability to find an EHR solution or components at an affordable cost; difficulty in creating a migration plan from paper to electronic health records; and difficulty in finding a satisfactory EHR solution that is not fragmented over several vendors or IT platforms were given as the top five barriers to EHR implementation.(20)

In A Proposal for Electronic Medical Records in U.S. Primary Care, the authors point to the transience of vendors as a barrier, since many have gone out of business or are in financial trouble.(21) As a result, many general practitioners view EHR implementation as risky, especially since there is currently no data standards in place that would facilitate a legacy move from a 'one-of-a-kind system' to another in the future.

Denis Protti is an expert on UK electronic health record initiatives. In The EHR Journey in the UK: Change in Direction? he points to several impediments:(22)

In Towards Personal Health Record: Current Situation, Obstacles and Trends in Implementation of Electronic Healthcare Records in Europe, Iakovidis provides a list of barriers to implementation and gives reasons for why there are so few electronic healthcare record systems:(23)

Waegemann maintains that change management remains the main hurdle:(26) Changing the way physicians collect and disseminate information about patients is quite difficult. What's the motivation for them to stop writing their notes and instead, use hardware and software that is not easy to use and which could possibly make their days longer? Reducing physician resistance is key. Lack of perceived benefits and lack of direct motivations are factors. Proving the measurable benefits of electronic health record systems is not an easy task, especially when most are first generation. Many physicians ask why they should invest substantial amounts of money. The many benefits, including reduction of errors, must be explained to them.

One of the main barriers to implementing electronic health record systems is the lack of standards. The ability to search for, access, accurately interpret, and administer large volumes of health information is dependent on the widespread use of agreed standards. Without them, it is very difficult to share information, which is one of the main reasons for implementation. Such standards include: data standards and terminologies/controlled vocabularies; data interchange and communication standards; architecture standards; imaging standards; security standards; and entity identification standards. Many healthcare professionals and organizations are currently involved in the development of standards.

A conceptual framework is needed that incorporates the standardization of patient identifiers, clinical vocabulary, and data architecture.(27) This will allow physicians with various specialties and from different parts of the world, using a variety of EHR systems, to share patient information and work together to offer better care and continuity of care. Currently, many experts believe that we are still far away from a platform adequate enough to allow for thorough interoperability and also, data integrity.(28)

In Standards for the Electronic Health Record Emerging from Health Care's Tower of Babel, the authors state that Health Level Seven (HL7) is seen as the principal messaging standard for clinical data in the U.S., and possibly, the world.(29) The National Center for Vital and Health Statistics (U.S.) suggests using HL7 for clinical messaging. An endorsement of this standard by Health and Human Services would be a major step for electronic health record systems in the United States,(30) a step that is particularly needed for data architecture and data exchange standards since the passage of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. The legislation is requesting agreement for standards and to have them in place as quickly as possible.

HL7 is also the official New Zealand standard for all clinical messaging. It was recommended by the data project team of New Zealand's WAVE (Working to Add Value through E-information) initiative that was created to enable the exchange of high-quality information between healthcare providers, as part of a commitment to provide better care for New Zealanders. Common messaging standards are required to enable communication across unlike systems with information in a variety of data formats. HL7 data model has several advantages, including: it is non-proprietary; it is seen as a standard and is used internationally for healthcare messaging; it incorporates XML, which is also non-proprietary; and it can provide a tight link between inter- system messages and the data model.(31) READ v237 is recommended for use in primary care diagnoses and procedures because it provides more detail than the ICD-10 codes. However, many organizations are upgrading directly to the SNOMED-CT system.(32)

Currently, in Europe, it looks as though an XML-based architecture is the best choice for the sharing of health information because of its universality.(33) The most significant projects since the completion of the GEHR (Good Electronic Health Record) three year project ended in 1995 are Synapses; EHCR Support Action (EHCR SupA); and SynEx.(34) In particular, the Synapses project is getting a lot of attention. Its architecture creates a virtual EHR system that facilitates data sharing between platforms. Based upon the concept of a centralized computer, it facilitates the transfer of health data from many different systems and platforms by acting as a translator between the various protocols. Synapses overcomes many of the obstacles associated with the sharing of electronic information through distributed systems.

The United Kingdom's NHS is also interested in the adoption of international healthcare standards for the implementation of electronic health record systems. As part of their e-government strategy they are utilizing e-GIF, which is the e-Government Interoperability Framework.(35) e-GIF standardizes and defines the government's technical policies with the goal of realizing information systems interoperability throughout the public sector; Internet alignment through the adoption of common standards; the adoption of XML; and the use of the browser for the main interface, making information much more accessible. What that means is a migration to SMTP from X.400 for email, and to XML from EDIFACT for messaging. The NHS is implementing eSMTP email transfer protocol to eliminate problems resulting from the combined use of SMTP and X.400 messaging environments.

SNOMED (Systemized Nomenclature of Medicine) is a joint collaboration of the NHS Information Authority and the College of American Pathologists in the U.S. that created a standardized clinical terminology that healthcare professionals can use to improve the compatibility of data. The NHS uses SNOMED CT, along with UKCPRS and HRGs for terminology and classifications. HL7, Version 3 and DICOM make up the schema chosen by NHS for its electronic health records initiatives, and ISO17799 for security.(36)

Two specific standards of particular interest in relation to Australia's HealthConnect are HL7 (Health Level 7) and the Good Electronic Health Record (GEHR). GEHR is a standardized architecture for electronic health records that provides a method for the encoding of specific clinical information without the need to prescribe it first. HL7 is the dominant clinical messaging standard in the U.S. and is in widespread use in Australia because of its flexibility. Its numerous optional data elements and data segments make it adaptable to almost any site. However, this same flexibility also creates problems that make uniformity difficult. HL7, Version 3, a new version of HL7, addresses these problems by the incorporation of a well- defined methodology based on a reference information model, making it much more suitable for electronic health record systems.

The Veterans Health Administration and Internet 2 in the United States; the National Health Service in the United Kingdom; the National ICT Institute for Healthcare in Holland; and the Ministry for Health in Brazil have all expressed interest in the XML-based electronic health record system that is currently under development for HealthConnect, Australia.(37) The design and software will be available for free through the openEHR Foundation to encourage its use and testing by the international health community. The system will be based on openEHR, which is an improved version of the very popular Good Electronic Health Record (GEHR) architecture, and makes use of archetypes to solve the problems associated with interoperability and future proofing.

Understanding what the barriers are brings us much closer to changing the manner in which healthcare is currently administered, and creating the future we know is possible. Learning through the mistakes of others and finding out what works and what does not, takes us even closer to our goal, and perhaps more importantly, further away from failure.

Identifying best practices and lessons learned for implementation, integration, and sustainability of EHR systems will allow Canada to become a world leader in e- health and assist other countries in offering better healthcare. This document outlines the latest available information on best practices for electronic health records in the United States, Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and Europe from a review of the literature.

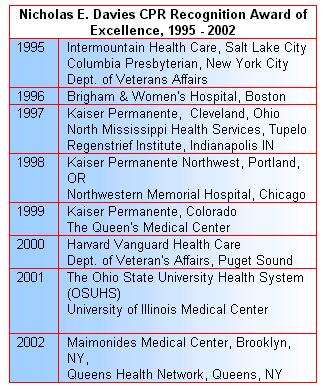

Although there is a low rate of physician adoption levels for EHR implementation in the United States, some of the most successful and long-term initiatives can be found there in hospitals and within health care organizations. What can we learn from these organizations, some of which implemented electronic health record initiatives more than ten years ago and are winners of the Nicholas E. Davies CPR Recognition Award of Excellence?(38) All award winners had one thing in common: they were committed to changing work processes, which is a very complex undertaking, and includes insisting that physicians use computers.(39) Protti also points out that physicians must be included in all stages of implementation to keep the focus on clinical care needs, and be supported by CEOs and senior physicians -- two of the factors consistently associated with success.(40)

The best EHR implementations share some other common features and practices. What is the one factor above all others that is essential for success? Physician support.(41) Physician involvement is also critical, especially when it is supported with sustained leadership from a practicing physician who has credibility with peers, and who views the EHR system as an enabler of clinical practice improvements.(42) Expecting to re- engineer some work processes before implementation, and having change management and system evaluation plans in place is essential because stakeholder flexibility to adapt to organizational change is crucial.(43)

In Understanding the Paper Health Record in Practice: Implications for EHRs, Fitzpatrick goes one step further by asking, 'how do we support clinical practice?' instead of 'how do we get good data.'(44) If we really want to change the healthcare system and implement a national electronic health record for all citizens, and if we expect physicians to change the way they work, we need to understand the fundamentals of physician practice. If not, it will be like trying to fit the square peg into the round hole. In the author's words:

Any move to introduce technology into health care radically impacts the very nature of that care. If we don't have better understandings of the richness and complexity in the practical accomplishment of work, then we won't be able to design effective systems that will fit in with work. Furthermore, we won't be able to evolve work practices to take advantage of what technology can offer to support that work.(45)

Understanding how the paper record is used is integral for successful design of EHRs.(46) What's also integral is understanding that the health record is made up of much more than the data it contains, it is also representational of the web of relationships that exist between the healthcare professionals and the multiple parts that make up the complex world of medicine.(47) If we forget this, we set ourselves up for disaster.

By using information and communication technology, and knowledge management, we can improve healthcare, but it starts first with changing the way healthcare professionals think about the work they do, and asking them for a commitment to foster cultural change and accept information technologies. Change management needs to accompany any significant changes to work processes brought about by the adoption of new technologies. The complexity of the healthcare system makes this an even bigger requirement. Waegemann asks us to consider the following:

It may be time to step back and consider why thousands of people have not been able to make more progress regarding standardizing the EHR. Is it possible that we got it all wrong? We should not focus on recording and documentation but on processes. In other words, it may be beneficial to standardize processes rather than the documented outcome of processes, - which is the electronic health record. Other industries have focused on processes more than on documenting that process. If we understand the processes of using technology in patient care better, then documentation is secondary. Documentation is a direct result of the process.(48)

In The Electronic Medical Record: Promises and Perils, a paper presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology national meeting in May 2001, Masys advises:(49) that developing a practical view of EHRs, and having a conviction that healthcare is an information business, starting at the top, are key strategies, especially when one considers how much decision support is added to healthcare organizations when EHRs are implemented. System developers help the process along greatly when they act as coaches and troubleshooters, particularly when stakeholder orientation, user feedback sessions, and focus groups are built-in to an initiative. Incremental implementation, with each increment focusing on overcoming specific barriers to care, is really a good approach to take because it allows EHR projects to be accountable by reaching expected milestones.

Masys rightly points out that successful initiatives are not necessarily subjected to ROI analysis in the early stages, and it helps budgets a lot when implementation occurs in steps rather than in widespread sweeps.(50) Also, be prepared to modify commercial off-the-shelf software to integrate local functionality, and focus on standards-based data architecture rather than specific applications. User acceptance and adoption depend more on content and value than on presentation. Systems that are fast, reliable, and easy to use go a long way to create user acceptance and speed up adoption, as do content and value.

Kaiser Permanente is one of America's leading integrated health care organizations and was founded in 1945. Kaiser is found in nine states and the District of Columbia with over eight million members, over 50,000 clinicians, over 11,000 physicians, 29 medical centers and over 40 medical offices. Kaiser's revenues in 2001 was approximately $20 billion.(51) Three of Kaiser's regional healthcare groups, those in Ohio, Colorado and Oregon, have won the much coveted Nicholas E. Davies CPR Recognition Award of Excellence for the implementation of successful electronic health record systems. By the mid-1990s, Kaiser decided to implement its EHR system, which they call KP-CIS (CIS stands for Clinical Information System), in all of its clinics.(52)

What are some of the main lessons learned from Kaiser's experience?(53)

Other lessons to be learned/guiding principles from Kaiser Permanente are equally as important and include:(54) making sure that physicians and staff members believe that it will facilitate better care for patients, while enhancing relationships with them. The project team must be made up of practicing physicians and other staff members to ensure that local preferences and workflow processes are incorporated; clinical utility is high; and credibility with other staff is strong. Leaders and sponsors who offer support to users, are available, and very visible are also key. Ongoing involvement of physicians and staff members is required for the development, implementation, and maintenance stages of an initiative.(55)

Physicians need to realize that taking their place in the design and development of electronic health record systems will help to create the future of healthcare. Many existing systems do not support clinical use and were designed, for the most part, to support the financial side and management of healthcare, including billing and audits, and not patient care.(56) Fitzpatrick agrees. He emphasizes the importance of practitioners -- including those from nursing and allied health sectors -- making their voices heard by analyzing their work processes and subtleties that accompany it, and having them integrated into the design of future electronic health record systems.(57) Goorman and associates state that one of the main reasons why EHR implementation is problematic in practice, is because the models used to develop the systems are not based on how the work of physicians and nurses is actually performed, but rather, on how others think it should be carried out.(58)

Training must also be provided and based on individual learning styles for adoption to occur, and all users require honest, timely, and regular communication every step of the way. In addition, EHR implementations must be given realistic time frames that focus on point of care usability issues.(59)

As can be seen, the U.S. is helping to create a new future for healthcare through the establishment of best practices. Waegemann says that good and steady progress is being made in the United States, one block at a time:

In the US, a reality has set in that the original vision of the CPR is unrealistic for the near future. It featured a concept more than a system, because there is such a dramatic difference between different types of healthcare records. Rather than having one system attempt to do all of these functions, a healthcare provider's journey toward an electronic health record system is in the strategic implementation of these building blocks. In the United States, progress is being made on the component level rather than on the overall concept. The question should not be, "Who has implemented electronic health records?" but "What components toward electronic health records have been implemented?" When considering the progress made in components, one sees that providers have varying priorities and have established different implementation paths. The level of information infrastructure, standards, and functionality vary in the main regions of the world.(60)

Australia is dedicated to the development of a lifetime electronic health record for all its citizens. HealthConnect is the major national EHR initiative in Australia, and is made up of territory, state, and federal governments. MediConnect is a related program that provides an electronic medication record to keep track of patient prescriptions and provide stakeholders with drug alerts to avoid errors in prescribing.

Although Australia has invested a significant amount of money into the computerization of its healthcare sector, it has run into a number of problems, including those associated with fragmentation, scalability, and inaccessibility.(61) International research was conducted by PriceWaterhouseCoopers in an effort to gauge Australia's position in regards to healthcare, and to give direction for next steps. Here are some best practices from countries, such as Denmark, Germany, France, Canada, and the United Kingdom, which are seen as benchmarkers:(62)

Information and communication technologies tend to flatten organisations and may not mesh well with the rigidly defined job roles and hierarchical structure of current medical practice. Many types of organisational changes will emerge throughout the health care system if information technologies are widely adopted.(63)

Flinders University researchers analyzed electronic health record initiatives in New Zealand in an effort to find out what Australia could learn about building a national approach to EHRs. Some of the building blocks include: (64) developing legislation that balances the protection of patient privacy, with allowing healthcare professionals access to information. Regulations to ensure that security mechanisms necessary to achieve this balance must be approved by all stakeholders. To launch a successful EHR system, you need a central national health identifier, which provides a common framework and view of patients, and a national coding system for primary care. New Zealand has a centralized decision- making organization that takes on a national approach to electronic health record implementation. This is important and encourages progress. Any country with a national healthcare system can learn a lot about EHR implementations from New Zealand.

Technological systems are not perfect, but they can be tweaked and changed to facilitate use and remove some of the technical difficulties associated with implementation. Changing people is often not as simple. The Australian National Electronic Health Taskforce states, "most implementation issues revolve around human rather than technical considerations, and can thus be addressed. Thus 'people problems' are recognized as more important than 'technical problems'":(65)

State governments in Australia are also heavily involved in the development and implementation of EHRs, and one of the most advanced is New South Wales' NSW EHR*Net.(66) Its goal is to provide access to health records through a web browser. The New South Wales Advisory Committee on Privacy and Health Information reports:(67) that Australia has much to learn from overseas initiatives, including the development of widely accepted privacy and security legislation, which is needed to meet public expectations. To increase awareness concerning the issues and problems associated with electronic health information security and privacy, public policy debates are needed. Best practices also see the incorporation of unique patient identifiers applied across the system and used strictly for e-health. Stakeholders need to have input in all stages of development to gain wide public support and integration.

According to the October 1, 2001 issue of Harris Interactive Health Care newsletter, U.S. Trails Other English Speaking Countries in Use of Electronic Medical Records and Electronic Prescribing, and using data from the Commonwealth Fund/Harvard School of Public Health/Harris Interactive, only 25% of primary care physicians in Australia use an electronic patient record and only 13% of its specialists.(68) To increase the EHR adoption rates for its physicians, Australia can take some advice from the United Kingdom:(69) It is important to increase the level of education and training for GPs and specialists, and provide them with skilled IT support. Developing a business case for EHRs will increase use among physicians, who often cannot rationalize the expense of installation. Also, encouraging physicians to use a common data model will allow them to more easily share patient data, which is of course, one of the main reasons for implementing an EHR. Importantly, to encourage the sharing of patient data, a national coding scheme obviously makes a lot of sense, as do validation and verification procedures to create better quality data. And finally, security and confidentiality issues must be fully addressed for successful implementation because GPs are fearful that without legislation, they will increase the likelihood of lawsuits against them.

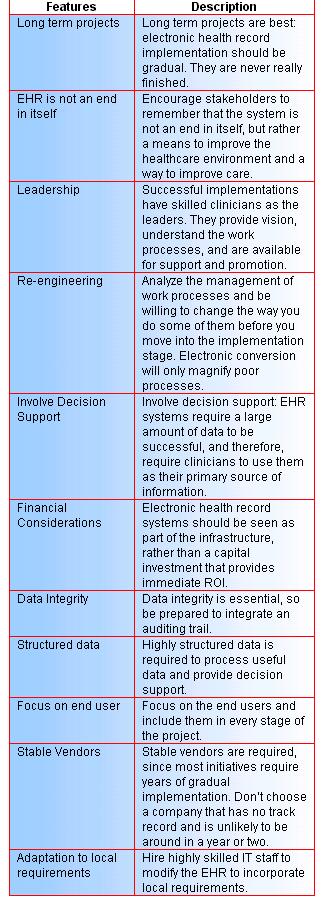

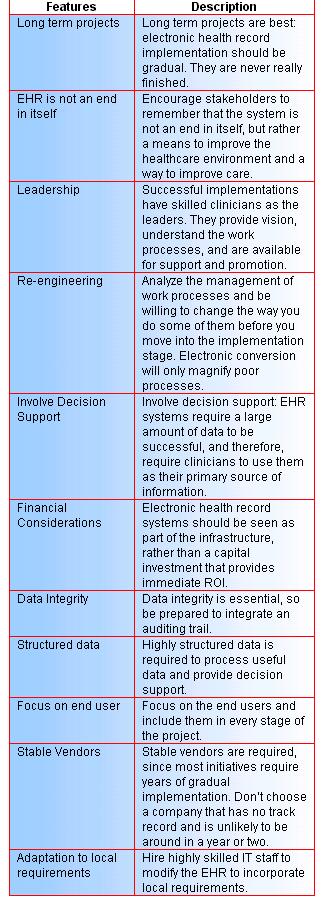

The following table, which features practices of successful electronic health record system implementations, was developed from information in The Benefits and Difficulties of Introducing a National Approach to Electronic Health Records in Australia:(70)

To date, Australia has learned a lot about advancing the development and implementation of EHRs, with more trials planned for later this year. Australia has a long term commitment and is beginning to establish itself as a world leader in regards to research and evaluation of electronic health records.

New Zealand is well positioned in terms of electronic health records, and is considered by some as the country on the verge of making the greatest breakthroughs in healthcare reform. Why? New Zealand has already made progress in some key areas, namely: in the provision of unique patient identifiers, and privacy legislation, two important building blocks needed for the implementation of a national EHR program.

New Zealand first introduced its National Health Index (NHI) patient identification initiative in 1977, and the seven character identifier is currently used in both primary and secondary care. In addition, the New Zealand Privacy Act (1993) and the New Zealand Health Privacy Code (1994) have specific policies implemented regarding the collection, use, and access of personal health information; disclosure; and security.(71)

Another healthcare information system considered ground-breaking is the Medical Warnings System (MWS), managed by the New Zealand Health Information Service (NZHIS). The MWS consists of medical warnings and alerts, healthcare event summaries, donor instructions, and next of kin contact information.(72) The MWS is designed to provide healthcare professionals with access to any known factors that could increase the risk of patient injury.

The New Zealand Ministry of Health also created Wave (Working to Add Value through E-information) in 2000, with a mandate to analyze the state of health information management in hopes of offering better care to New Zealanders. Much of the information in the following section is derived from Wave research.

Primary care practices in New Zealand have a relatively high number of EHRs in place, and therefore, the country has sufficient infrastructure to support a national implementation in the future.(73) According to U.S. Trails Other English Speaking Countries in Use of Electronic Medical Records and Electronic Prescribing, 52% of primary care physicians in New Zealand use an electronic patient record.(74) Further data shows that 52% of New Zealand physicians are using electronic prescribing systems often.(75) New Zealand also has a centralized decision-making organization that takes on a national approach to electronic health record implementation, which is important and encourages progress. It is one of the few countries in the world which has made any attempt to develop a national EHR standard, but it has a long way to go. By learning from projects in the United Kingdom, several issues are raised that New Zealand should take into account when moving forward to its goal for a national EHR roll-out:(76)

New Zealand providers who adopted electronic record keeping early on are becoming vocal over the current system's shortcomings in providing a platform for integrating their patients' care. We can use this information to develop best practices:(77)

Adequate, timely, and accurate health information is a basic requirement for success, by integrating health information from multiple sources. While still supporting clinical best practices, it is crucial to understand that work processes are significantly altered when EHR systems are introduced, and that is one of the reasons incremental rollout is the preferred option for implementation of EHRs. In The Mantra of Modeling and the Forgotten Powers of Paper: A Sociotechnical View on the Development of Process-oriented ICT in Health Care, Berg and Toussain explain that ICT can actually be a coordinating and accumulating tool-in-development, and can be used as an agent of organizational change.(78) The resulting disruption is kept to a minimum, helping stakeholders integrate with the technology and process the change.(79) Of course, risk of inconsistencies is heightened when a national approach is not taken, but most countries are willing to risk it.(80)

Other best practices outlined in From Strategy to Reality: The WAVE Project, include:(81)

In summary, New Zealand has a firm foundation in place for the adoption of a national EHR. Its single-tiered government system will make the process an easier one in some ways,(82) as will the dedicated officials within the NZHIS and the Ministry of Health, whose significant amount of work and dedication is noted by the international community.

In the late 1980s, the United Kingdom initiated a national health information strategy, with an agenda to research, develop, and implement health informatics policies and technologies. For the last six years, the National Health Service (NHS) information strategy: Information for Health, has focused on EHRs as one way to transform the healthcare system into a vehicle for patient empowerment. The NHS also encourages GP practices to utilize information management systems and has implemented a GP computer systems accreditation policy to encourage the use of EHRs.

The U.K. government also has a long term commitment to electronic health record development and implementation through its Electronic Record Development and Implementation Programme (ERDIP), which has a mandate to learn everything there is to know through the creation of local EHR initiatives. In all, nineteen ERDIP sites were announced and implemented, seven of which were nearing completion by mid 2002.(83)

One of the original intentions of ERDIP (Electronic Records Development and Implementation Programme) was the collection of lessons learned. The goal was to use the lessons learned to bring about organizational change for long-term success. Protti asks if anyone is doing this?(84) Analyzation and evaluation of the material is necessary. He points out that,

The challenge for the future NHS is to translate an increasingly greater knowledge of the relationship between social, clinical and technical issues into effective patient-centered systems that operate across transient organisational boundaries.(85)

In ERDIP EHR Issues and Lessons Learned Report, a document released by the NHS Information Authority, the author points out that although work has progressed steadily along in the local EHR initiatives, with immediate requirements addressed, he wonders if the bigger picture somehow got lost along the way. (86) Concentrating on the local but with an eye always to the bigger picture is important, especially since there is a real need to take the knowledge gathered locally and share it to inform national initiatives. Systems thinking is needed to move from the local to the national, and to make decisions about issues such as security and privacy, while still keeping international implications in mind.(87)

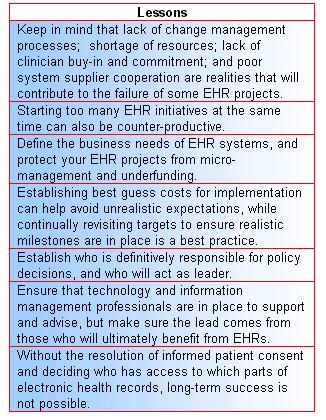

Here are some lessons learned that focus on national requirements from the ERDIP EHR Issues and Lessons Learned Report:(88)

It is important to point out that while it is extremely helpful to uncover and analyze lessons learned from local/regional initiatives, it is also equally or more important to consider scale. Can an EHR project in Devonshire, for instance, be projected onto a larger regional or even national system? Is the infrastructure so entirely different that what works locally might not necessarily work as a national solution, because issues and problems differ so greatly?(89) Are some of the successful local initiatives even feasible nationally?

In Implementing Information For Health: Even More Challenging Than Expected, a report written to review the state of progress of Information for Health, and to consider the implications resulting from the wide range of ERDIP initiatives, the following lessons learned are noted:(90)

As Denis Protti points out: "the EHR journey is taking the NHS through terrain more complex than expected,"(91) but it continues, with people from many countries working for a new future in healthcare provision. The U.K. has spent billions of dollars on its bid for electronic healthcare reform, and has achieved great success with 87% of U.K. physicians using electronic prescribing systems often.(92) It will be interesting to see what it decides to do next.

European governments are working together to change healthcare and offer an integrated system. There are two main reasons why the European Parliament and other EU institutions are pushing for the creation of a European electronic health card:(93)

Several joint projects in Europe are underway, including Cardlink 2 (Ireland, Germany, Holland, Spain, Greece, Portugal, France, Italy, Finland), which is developing a medical emergency health card; Diabcard (Spain, Greece, Italy), in the advanced stages of a diabetic health card; and G-8 Healthcare Data Card Project (France, Germany, Italy, Canada, UK, USA, Japan, Russia), an initiative to develop an international medical emergency card, with the capability of allowing secure access for healthcare professionals and the creation of administrative data.(94)

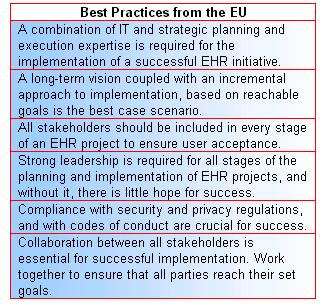

The European Commission has studied the implementation of electronic health records systems in the EU, and developed a number of best practice guidelines from the information collected:(95)

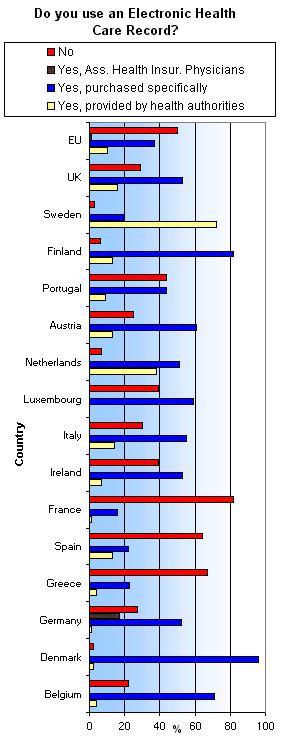

According to the European Commission(96) (see chart below), Sweden is the EU country with the highest percentage of EHCRs, that are provided by health authorities, at 72%. It was also the only country above 50%, with the Netherlands the next highest at 38%. The EU average was only 10%.

The EU country with the highest percentage of EHCRs purchased specifically was Demark with 96%, and the next highest was Finland with 82%. The EU average was 37%.

The percentage of respondents saying they do not use EHCRs was highest for France, with 82%, and next highest was from Greece with 67%. Of the countries whose respondents replied that they did not use EHCRs, the lowest were from Denmark, 2%, Sweden, 3%, and the Netherlands, 7%. The EU average of respondents who do not use EHCRs was 50%.

Iakovidis points out(97) that step by step is best using a well-thought out strategy, coupled with the understanding that EHR systems are more about information management than information technology. Large scale, all at once implementations, run into problems because time is needed to overcome the fear that invariably comes with using new systems that re-engineer work processes. A study of electronic medical records systems in Norwegian hospitals, especially in the largest hospitals, reveals that there is a low level of use by physicians. They utilized less than half of the functionality possible.(98) In addition, existing work routines were reinforced, with no development of new or more advantageous ways of doing medical work, indicative that organizational and change management techniques need to be considered.(99)

That's why stakeholders need to work together, through misunderstandings and frustrations, because none of the parties involved can do it alone. Ensure the commitment of leaders and management since success depends on their involvement and commitment. Berg makes the point that implementation of an EHR brings about a mutual transformation of both the technology and the healthcare organization.(100) Furthermore, "the management of IS implementation processes is a careful balancing act between initiating organizational change, and drawing upon IS as a change agent, without attempting to pre-specify and control this process. Accepting, and even drawing upon, this inevitable uncertainty might be the hardest lesson to learn."(101)

Also important is using an architecture that accommodates ever increasing amounts of data that can be shared and viewed by all professionals in and outside hospitals, including standardized terminology and coding to provide meaning for the data in the healthcare records and allow them to communicate in different languages. Making sure the systems are user-friendly, and securing experienced help from external experts can make a big difference. Confidentiality and security (legal and ethical) issues need to be addressed before wider implementation is possible. Finally, remember that commitment is especially needed after the initial implementation stage.(102) Do not just set it up!

Europe has much to offer the world of international EHR development and implementation, and has a lot riding on getting it right. The EU is very open to sharing the information it has learned along the way, and is also eager to participate in joint EHR projects, which makes for an exciting next couple of years for healthcare.

Computer technology has fundamentally and significantly changed society, the way in which people live, and especially how governments are run, including how healthcare is managed. Reformation of healthcare systems across the world through the use of ICTs and knowledge management in the form of electronic health records will pave the way for many more improvements in the future. For now, the focus must be on learning from successes and failures, and then moving on to the next stage. As was shown in the review of best practices and lessons learned, there is a great deal of repetition when looking at what works and what is needed in the countries studied. That is an indication of how much work has already taken place over the last few years. Of course, knowing what works and what doesn't is only half the battle won.

What's more problematic is taking it to the next level. For instance, knowing that successful EHR initiatives require physician support and visionary leadership is one thing, it is quite another to gain the support of physicians and have visionary leaders step up and accept the challenge. Realizing that without the best privacy and security measures in place, electronic health record systems will not have a chance to succeed is one thing, getting legislation passed that all stakeholders can agree with, is another, especially when there is so much pressure on government to make sure that it does everything possible to protect information.

Government systems are under tremendous stress from electronic technologies, in part, because of the rapid changes that seem to go hand in hand with technology, and which cause rapid changes in the structure of government departments and policies. Often, quick decisions are wanted, and perhaps needed, but are not always easy to come up with. The complex duality is obvious: we must forge quickly ahead on some levels to bring the future closer for our healthcare systems, but we must also tread carefully and scout out the territory to avoid heading in the wrong direction.

Related Papers

Electronic Health Record Resources