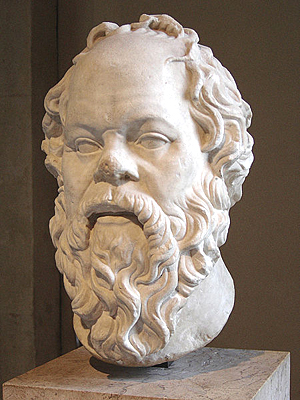

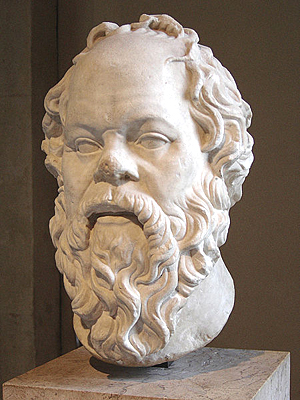

Socrates

Socrates did not "think it is permitted that a better man be harmed by a worse."(1) He also felt that he would be harmed if forced into prison, or exile, and especially, if he was silenced.(2) Did Socrates make contradictory statements?

Socrates believed that a division existed between the body and soul: the individual is the soul, which has a body to house it, enabling it to live on this planet. Therefore, even if he was killed, Socrates was sure that he would not be harmed. His body would cease to exist, but the soul would just move on to another place.(3) He also claimed that the only harm that could come to a person was spiritual harm, and that was only through an individual's own wrong actions. Socrates thought that Meletus and Anytus were hurting themselves by asking for his execution, but a good person could not be harmed by another who is worse.(4)

If Socrates was found guilty, there were five possible options open to him: prison, exile, silence, a fine, or death.(5) Imprisonment was not even a consideration for him because he would always have to live his life under the orders of others.(6) Banishment was an option that some of Socrates' contemporaries would choose. For them, exile was better than death, but to a proud Athenian like Socrates, who so identified himself with his polis that he had only left it for military service and a trip to the Delphic Oracle -- for him to leave his beloved city after seventy years would prove impossible. Socrates also reasoned that no matter where he went, the citizens would find his "company and conversation" unbearable, and he would be left to wander from one place to another, unable to settle anywhere.(7)

Silence may have been a consideration for the jury, but to Socrates it would have meant death.(8) He would be going against his daimonion or spiritual guide that helped him live his life. By keeping quiet, it would mean disobeying the gods.(9) To Socrates, "virtue was knowledge," and the only way to reach it was through questioning people's beliefs: searching for answers to the mysteries of life.(10) For him, "the unexamined life was not worth living,"(11) and therefore, silence would be harmeful to him. It would go against the gods, who had not given him any sign that he should fear death.(12)

It is true that Socrates could have paid a fine, but he did not have an amount of money that would be of interest to the jury.(13) Death seemed to be the only possibility for him. Prison, exile, and silence would cause him harm; they would hurt his soul, and he could not willingly do that to himself. Socrates would not harm himself willingly, even if it meant his own death. He strongly believed that no one does wrong willingly.(14)

For Socrates, death held the possibility of hope.(15) His soul would move to a new location and who could tell all the unknown joys that may be coming.(16) Maybe he would have the pleasure of discussing justice or goodness with Agamemnon or Hesiod. Socrates could not fear death because it would be "to think oneself wise when one is not,(17) ... and surely it is the most blameworthy ignorance to believe that one knows what one does not."(18)

So, Socrates did not make two contradictory statements. He thought that his soul might survive the death of his body, but it would be harmful if he chose to live his life with the full knowledge that he had made a wrong choice willingly. Of course, one problem remains that clouds the rest: if silence, banishment and imprisonment will harm Socrates' soul, and Meletus and Anytus have the power to inflict these punishments on him, then doesn't it seem that worse men can harm a better man?

Related Papers

Hellenistic World: Alexander the Great and the Spread of Greco-Macedonian Culture